Conservation is often perceived as meaningful and purpose driven work, yet it remains one of the lowest paid professional sectors. Despite people having (multiple) degrees and experience, there is often a lack of paid work plus you are kind expected to work for free for years to get experience before being able to take on (low) paid work. This has been built into the system. It has become the norm. Plus even between the few paid roles, there are numerous volunteer roles and a lot of NGOs rely heavily on free labour to run their everyday operations.

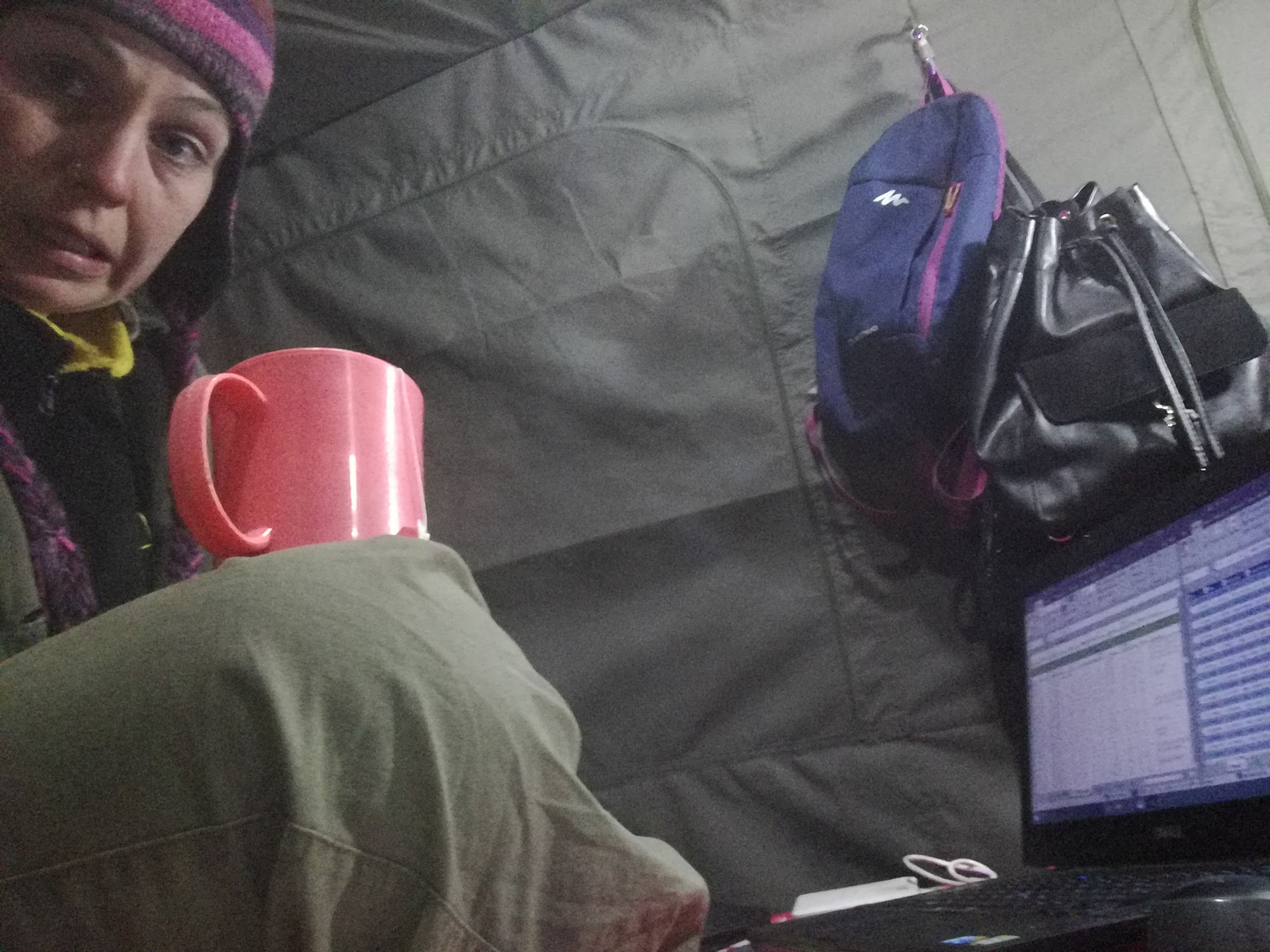

Conservation attracts highly motivated graduates as well as older career changers (who want to do something more meaningful with their careers) and people are willing to accept low pay for meaningful work. This oversupply of passionate applicants depresses wages, particularly in entry-level and field based roles. I myself have also done my time, I worked for years for free as a zoo keeper alongside my studies, as well as working as a chef part time for actual income. Then even after I graduated, my first role started off as I volunteer part time with an Ecological Consultancy associated with a Wildlife Trust. Thankfully I did not do too many free hours before they put me on the books as I was good. But still, all my work for the bat group and crayfish group in Nottinghamshire has been done as a volunteer, even though as part of these groups we are working to protect wildlife for all and for the future.

Why all this free labour? A key reason is funding. Most conservation roles sit within charities, NGOs or public bodies that depend on grants, donations or short term project funding rather than commercial business revenue. Unlike sectors that generate profit, conservation organisations reinvest limited income directly into land management, species protection and community work. There is also a lack of skills of making money within the sector, as many NGOs could generate income if they did things differently but that's a blog for another day. Salaries therefore compete with project delivery costs, and wage growth is constrained by unpredictable funding cycles. When grants are secured, they are frequently ring-fenced for specific outcomes, leaving little flexibility for staffing budgets.

Many positions require advanced qualifications, specialist licences and years of unpaid or seasonal experience, yet remain fixed-term or consultancy based. Public sector austerity in several countries has further reduced environmental budgets, shrinking permanent posts and increasing competition for stable employment. Many of my fellow students from both my Bachelors and Masters degrees went on to work in other fields. Especially those from the Bachelors. I was one of the few who knew this is for sure what I wanted to do and that nothing would get in my way. I was also lucky, whilst not rich, my parents were able to support me during tough times. When I was working low paid or free jobs, they would help me out as needed with necessities like my phone bill or car insurance. Not everyone has that luxury and so often conservation and wildlife jobs I general are seen as rich people work. That only the privileged can see it through as not everyone can work for years in unpaid roles whilst also going through academically intense settings.

Finally, despite conservation delivering long-term societal value, it is rarely reflected in market economics. Healthy ecosystems provide flood regulation, carbon storage and biodiversity benefits, yet these services are seldom monetised in ways that translate into secure salaries for those protecting them. In many cases, the imbalance goes further: some highly profitable industries extract natural resources, degrade habitats or generate pollution while externalising the environmental costs. The financial gains are privatised, while the ecological damage becomes a public burden. NGOs, charities and under-resourced public bodies are then left to restore habitats, mitigate impacts and repair biodiversity loss, often relying on short-term grants and donations to do so. As a result, conservation professionals carry significant responsibility, technical expertise and legal accountability, working to address problems created by far wealthier sectors, yet their remuneration remains modest compared with industries driven by direct financial return.